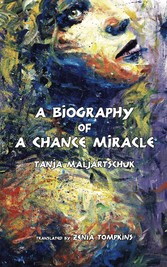

A Biography of a Chance Miracle

von: Tanja Maljartschuk

Cadmus Press, 2018

ISBN: 9784908793424

Sprache: Englisch

200 Seiten, Download: 3257 KB

Format: EPUB, auch als Online-Lesen

2 God in Heaven and on Earth

Sometime in the seventh grade, Lena began to have serious problems with her faith.

God, to whom Lena politely prayed every morning and every evening, suddenly lost all sway over her because she just couldn’t take him seriously anymore. Lena’s old grandma had told her about him. She had lent him to Lena for a while, to use until Lena found her own. Grandma taught Lena to pray, which she herself did before sunrise and after sunset without fail every day. Grandma had two Gods: One hung on the wall in the summer kitchen (Lena liked that one more) and the other in the room where she slept with Grandpa. Grandma prayed to the second one in the mornings and to the first one in the evenings, after she had washed her feet. Incidentally, Grandma never brushed her teeth. Lena figured out why only much later. She no longer had any.

In the evenings, Lena’s grandma would wash her face and feet, would take off her work clothes, and — thin as a rake, in just a nightgown that reached all the way to her heels — would fold her hands on her bosom and pray in a language unknown to Lena. The beginning was always identical and always came out as one word: “Arrfatherwhoartinheaven.” Lena, who didn’t wash her feet because she was lazy, would sit on the trestle bed next to her and listen. She liked her grandma’s God, which was exactly what she called him, “Grandma’s God.” He was strict but fair. He was almighty and looked very respectable. He was about sixty years old, and Lena found this to be the best age for a God — not too young because no one would listen to a little punk, and not too old because people would think that he was senile. This sixty-year-old God of Grandma’s had a magnificent beard and a gentle face, which could nonetheless change its demeanor depending on how much Lena had sinned over the course of the day.

She would often talk to him. Typically she would propose some kind of shady deals. For instance, you, God, give me this or that, and I’ll believe in you forever. As if it mattered to God that people believe in him.

Once in a while Lena would test him. She would say, for example, “There’s a candy in my mouth. Prove that you exist and make this candy fall out of my mouth. Then I’ll believe.”

And sometimes the candy would fall out.

Lena’s grandma made different kinds of deals. She would make requests on behalf of Lena and all her other children and grandchildren, without offering anything in return. She would also ask for nice weather and a good harvest. That the cow’s calving go smoothly and that the pigs stop demolishing the floor in the hog house. That Colorado beetles not devour the potatoes so brazenly. That the hay last till spring. That Grandpa drink less, and that everything go well for Lena’s parents so that they could finally buy the car they’d been dreaming of.

Grandma would always finish with the words, “I have sinned without measure. Forgive me, Lord.” Lena didn’t understand this part because Grandma never sinned. She was infinitely good and was satisfied with everything that she had, even though she always had little. People like that don’t exist anymore, Lena would say in time. These days people want everything, they only do what they want. But Grandma rejoiced in the very fact that she was healthy and still kicking.

Grandma didn’t have any teeth, and now and then, when she got an awful hankering to eat a pickle, she would grate one on a fine grater and would gulp it down like porridge. Her desires were very modest, and if they weren’t satisfied, then Grandma didn’t particularly suffer.

Lena’s grandpa, now he was a completely different story. He had, truth be told, only two desires: to drink and to smoke. These desires were strong enough that in his old age, when his God had ceased fulfilling them, Grandpa took vengeance and stopped believing in him. He lay helplessly in his room, without a cigarette or a tumbler of moonshine, and would see demons.

That was when Lena promised herself that she would never desire anything too much because she didn’t want to meet these demons herself.

Lena prayed every morning and every evening for many years. If she unexpectedly forgot to do so for some reason, she would torment herself and dread getting punished. She would think to herself, well, that’s it, I won’t be able to buy a cup of ice cream or a pastry on Sunday, or I’ll make some stupid mistake on a test and get a B in Ukrainian grammar for the semester. Or, most likely, I’ll just fall into a puddle somewhere in the street and half the town will laugh at me.

Grandma’s God saw everything and forgave nothing. He sat inside Lena and watched over everything that she did and thought. And if she did or thought something bad, she always got what she deserved.

Lena lost her favorite mittens because she didn’t want to help her mom tidy up the apartment. Lena couldn’t figure out how a protractor worked because she had silently called her dad “stupid” the night before and said, “When I grow up, I’ll get back at you.”

Everything was interconnected like this. The relationship of cause and effect functioned predictably, like an adding machine. Lena would obediently accept her punishment and continue on with her childish sinning.

“This was a type of pastime,” Lena would later write. “My childish God and I would wink at each other. I at him, and he at me. In this way neither of us got lonely.”

Till one day, sometime around age thirteen, Lena suddenly realized during a routine evening prayer that she didn’t feel anything anymore — neither fear of punishment nor gratitude for her existence. She realized that someone had pulled this borrowed childish God of hers off the wall, and now a big black hole that could in no way be shut gaped in his place. She realized that the game was over and that they were both now on their own. Do what you want, sin as much as you can: There will be no punishment for the bad and no reward for the good.

Lena stopped praying and nothing happened. The ground didn’t split open beneath her feet. A few more times, mostly out of force of habit, she involuntarily said to herself, “Forgive me that I no longer pray to you, God,” which was supposed to mean, “Forgive me, Lord, that I no longer believe in you.”

With time, Lena recognized the complete absurdity of such words and stopped making excuses for herself altogether. From the outside her life hadn’t changed. Well, except for the fact that once in a while Lena would try to convince her schoolteachers that God didn’t exist because she didn’t see him.

The so-called “public” God, if he did in fact exist, was also acting very weird and didn’t inspire trust in Lena. People who had for seventy years believed only in a bright socialist future all suddenly rushed in a hubbub to prostrate themselves in newly built churches. These churches differed from one another in nothing on the outside. Even after you stepped inside one, it was hard to figure out precisely what denomination and nationality that particular God was and how much he expected to be paid for salvation. Polytheism was in full bloom. There were Russian, Ukrainian, Orthodox, Greek and Roman Catholic, Protestant, Baptist and Evangelical Gods, even Gods of the Seventh-day Adventists and of the Warriors of the Kingdom.

In the last Soviet-style social housing neighborhood, which is where Lena grew up, five churches appeared, all of different denominations. Some people went here, others there. Old couples got married in churches after having lived together for forty years. Others got baptized in accordance with all the canons and rituals. Still others signed over all of their possessions to the church in blissful ecstasy. And they all stood together in confession lines on the eve of Easter.

Lena’s Christian Ethics teacher also led the entire class to confession. This was the one and only time that Lena publicly repented her sins.

The children were standing in a very long line, discussing their transgressions. Lena was very scared because she didn’t know what to say. That was when her classmate Ira helped her.

“This is what you have to say: I gave my parents attitude, I was lazy, and I thought ill of others.”

Lena repeated everything verbatim to the priest. The priest patted her on the head and ordered her to recite the Our Father twelve times.

“Excuse me,” Lena said to him in parting, “but I also don’t really believe in God.”

The priest didn’t even glance at her. He just said, “Then thirteen times.”

Lena’s uncle — actually, he wasn’t exactly related to her, but that’s a long story — not only didn’t pray himself but also preached against God whenever a convenient opportunity presented itself. And an opportunity would always present itself. He just couldn’t let it go. He was always trying to convince others that faith in God contradicted the principles of science.

Lena called him Doubting Thomas.

This sudden universal turn toward religion tormented her uncle more than his lack of money, the infertility of both his daughters, and the fact that his son had died in Afghanistan for no good reason. Waging war against God was in essence his profession. In the past, the uncle had taught atheism at the local university and, as rumor had it, also had a side gig working for the so-called “organs.”

What exactly these “organs” were, Lena didn’t know. She thought maybe it was a reference to some kind of underground hospital where they performed abortions on teenage girls or...